ADHD

Fluctuating and often fragmented relationship with attention, motivation, and regulation - not due to a lack of capacity, but inconsistency in its access. It is a condition of context-sensitive performance, where the brain struggles to filter, prioritize, and sustain engagement with tasks or experiences that lack immediate relevance, novelty, or emotional salience.

“ADHD is like having a Ferrari brain with bicycle brakes - powerful, fast, and driven by passion, but hard to slow down or steer in conventional ways.”

Screening and Evaluation of ADHD.

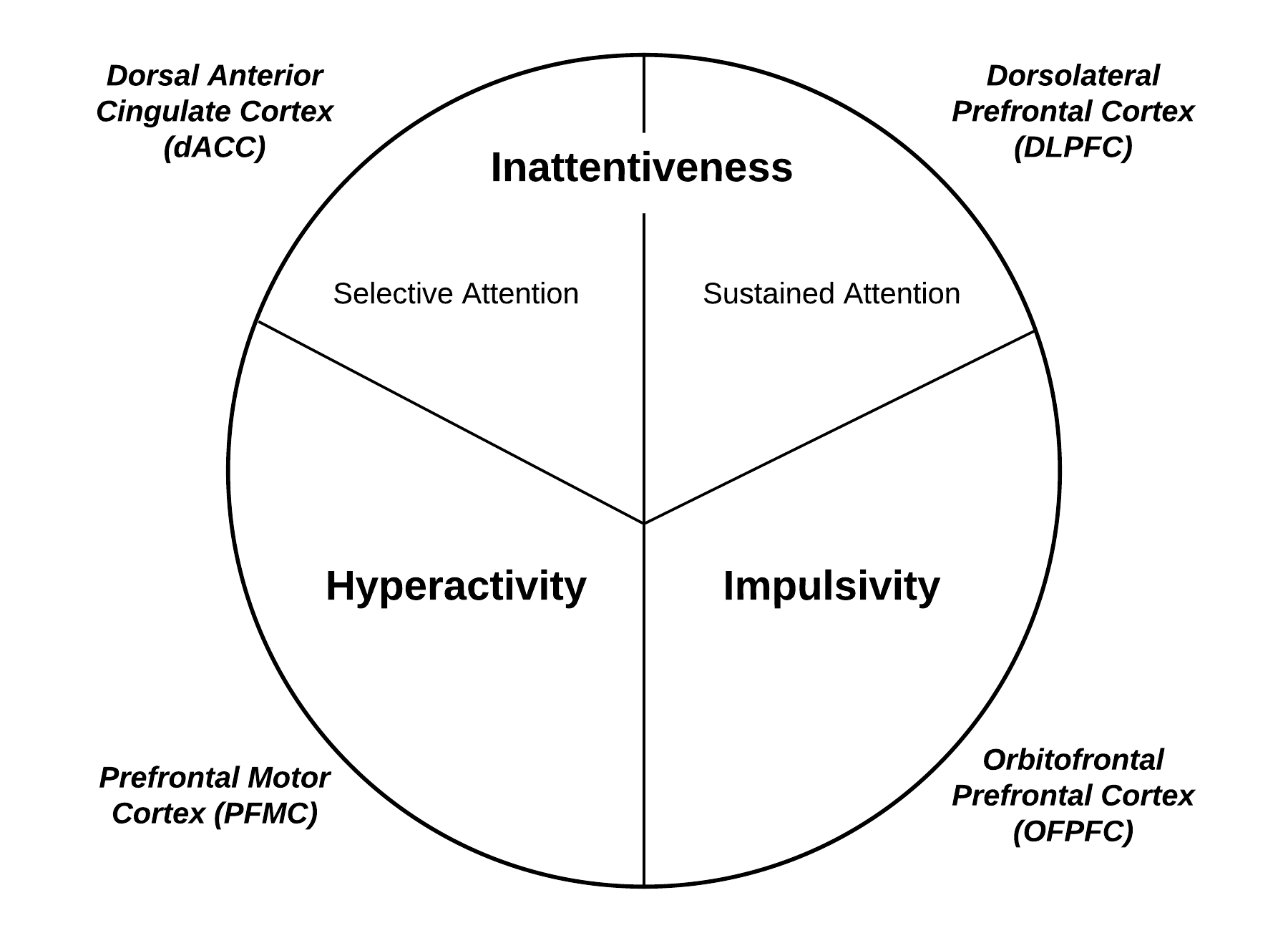

According to the DSM, ADHD symptoms can be divided into 3 domains, as shown in the image. According to the DSM, depending on age, 5-6 inattentiveness symptoms and/or 5-6 hyperactivity and impulsivity symptoms satisfy the diagnostic criteria for ADHD (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Collectively these symptoms are referred to as Executive Impairments.

In accordance with the symptoms shown in the image, there are several screening tools available to help evaluate for the presence of symptoms satisfying the DSM-5 criteria for ADHD.

One that I prefer is the ADHD-RS (this version is for adults) because of its ability to not only capture symptoms but also rate severity for symptom tracking over time with intervention.

As with many DSM-derived diagnostic labels, the diagnosis does not illuminate the underlying cause.

Researchers have pointed out that 116,220 combinations of symptoms can be derived from this that satisfy the criteria for diagnosis with 92% of these combinations being unique (Silk et al., 2019). While this speaks to significant diversity, it is not very comforting. Imagine 116,220 combinations of symptoms satisfying the criteria for pneumonia… imagine the difficulty in pointing to causation in this context.

What’s more, if you do the math, 40-60% of these combinations of symptoms overlap with other psychiatric disorders, meaning that between 46,000-70,000+ of these combinations are not unique to ADHD and may be indistinguishable from other diagnoses.

Some of the diagnoses that have overlapping symptoms (called differential diagnosis) include: Sensory/Processing Deficits (vision, hearing, speech), Specific Learning Disorders, Intellectual Disability, Substance Use, Sleep Disorders, Unipolar Depression, Bipolar Disorder, Anxiety Disorders, Trauma, Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder, Cluster B Personality Disorders (e.g., Borderline Personality, Narcissistic Personality, Antisocial Personality, Histrionic Personality), and Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder.

Beyond the DSM.

Expanding from the definition provided above, ADHD can be more aptly described as:

Not a deficit of attention - it’s a difficulty with regulating (or budgeting) attention (too little or too much).

Motivational wiring is interest-driven, not importance-driven.

Includes executive functioning challenges: organizing, planning, emotional regulation, task initiation, etc.

Time blindness, working memory lapses, and emotional reactivity are core to the experience.

ADHD is context-dependent - performance varies widely depending on the task and environment.

Often creative, divergent, intuitive thinkers who thrive in stimulating, flexible settings.

To more effectively explore the challenges of this experience, we must look beyond this diagnostic label and consider the whole person. Executive functioning is the terminal product (i.e., what we want or expect our brains to do for us); along the way, there are several areas of breakdown.

Causes and Contributions.

Psychology/Neurobiology. From a neurobiological perspective, ADHD arises from impairment in the communication between a number of brain networks or circuits. Below are the key brain areas within particular networks that are related to the key symptom domains:

It’s important to note that all of these areas are a part of the prefrontal cortex, the front and topmost region of the brain that is responsible for executive functioning. Because the executive part of the brain does not develop properly, ADHD becomes a “top-down” disorder, where the executive is not able to manage things such as impulse control and emotions.

Zooming in a little closer, we find that those with ADHD have difficulty “tuning the prefrontal cortex.” This tuning is maintained by the brain chemicals (neurotransmitters) dopamine and norepinephrine. Normally, there is a slow or tonic release of dopamine and norepinephrine, allowing for the appropriate transmission of signals (called transduction). Norepinephrine contributes to an increase in signaling, making appropriate connections. On the other hand, dopamine reduces noise to help decrease inappropriate connections.

In ADHD, there is an overall reduction in slow or tonic firing, leading to an increase in noise and a decrease in signaling.

The Body.

Perinatal. Some environmental risk factors associated with the development of ADHD include substance use during pregnancy, in-utero exposure to environmental toxins, low birth weight, and brain injury (Thapar et al., 2013).

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis. Stress and associated cortisol (stress hormone) fluctuation impairs the function of the hippocampus (responsible for memory) and cortices (responsible for executive functioning).

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis. Imbalances in estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone and certain metabolites of these main hormones may contribute to executive impairments. Imbalances in estrogen and progesterone in the context of perimenopause are associated with perimenopausal executive dysfunction.

Gut-Brain Axis. While the gut is an important influencer of neurobiological health, detoxification (as an extension of the gut) is intimately related to executive functioning. The inability to clear deleterious metabolites from the body leads to an interference in neural activities. Metabolites are generated from all of the work our bodies do throughout the day. Otherwise, toxins such as lead contribute significantly to executive impairment.

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid Axis. Hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism contribute to metabolic imbalances that impair cerebral energy mobilization, leading to executive impairment. Even “subclinical” changes in thyroid hormone can contribute to this. A full thyroid panel, including a TSH, T3, T4, and rT3, are essential for a comprehensive evaluation. Because the brain consumes a large portion of the energy in the body, imbalances in carbohydrate (glycemic or blood glucose dysregulation), protein, and fat metabolism can contribute to executive impairment.

Immune-Brain Axis. Inflammation, when it influences the brain, impairs the activity of dopamine and norepinephrine. Additionally, inflammation causes the shunting of serotonin, leading to depletion, which may contribute to emotion dysregulation. Finally, inflammation in the brain leads to the generation of toxic metabolites that degenerate and damage the brain in regions that are responsible for executive functioning.

Micronutrient Environment. The micronutrient environment is essential for executive functioning. Some specific deficiencies that strongly contribute to executive impairment include B12, zinc, copper, vitamin D, and iron, among others. For example, as iron levels decrease, there is a systematic decrease in IQ points which fortunately return after repletion.

Epigenetics. ADHD tends to run in families, with greater than 75% of individuals having a family history (Thapar et al., 2013). Those with a first-degree relative (e.g., mother or father) with ADHD are 2-8 times more likely to have ADHD. Beyond family history, specific genetic markers cannot be used for predictability as they are not consistently supported in research. Likely, the interaction of genes and environmental causes (aka epigenetics) contributes to the development of ADHD. There are specific genes related to executive impairment that can be evaluated and managed through epigenetic modification techniques.

Lifestyle/Environment.

Life Routine. Relational contexts (including interpersonal, leisure, work, etc.) that do not align with the ebb and flow of attentional budgeting and the interest-driven nature of those with ADHD symptoms are likely to involve conflict and challenges.

Nutrition. A diet not supporting micronutrients, carbohydrates, protein, and fat balance contributes significantly to executive impairment. Some of these imbalances were described in the previous section. Additionally, the Standard American Diet is highly inflammatory, contributing to executive impairment.

Exercise. A sedentary lifestyle or overall imbalance between activity and rest can contribute to executive impairment. A lack of exercise contributes to impaired frontal lobe and motor strip development, which are found to be impaired in the context of ADHD.

Sleep. Impaired sleep quality contributes significantly to an imbalance in the neurochemistry and energetic movement in the brain, contributing to executive impairment.

Substance Use and Addiction. Addiction (substances or behavioral) are common among those with ADHD. The interest-driven nature of those with ADHD is strongly associated with dopamine, a key neurochemical associated with addiction neurobiology. The use of substances often serves as a solution for an underlying problem, though the belief that improvement in ADHD symptoms in the context of stimulant use “confirms” ADHD is not true. Substance use can actually produce or provoke executive impairment.

Trauma. Childhood or developmental trauma is a leading cause of ADHD symptoms. Initially emerging as a protective defense, ADHD symptoms become pervasive and problematic over time. Therefore, treating trauma rooted in childhood may alleviate ADHD symptoms.

The Integrative Psychiatry Approach to ADHD.

Medications. The aim of medication treatment in the context of ADHD is to fine-tune dopamine and norepinephrine activity, improve blood flow, and support connection between impaired brain regions (improve networking). Medications for ADHD symptoms include two main categories: non-stimulants and stimulants. Non-stimulant options include guanfacine (Intuniv), clonidine, bupropion (Wellbutrin), atomoxetine (Strattera), and viloxazine (Quelbree). Stimulant options include two main categories: amphetamine and methylphenidate derivatives. Adderall and Vyvanse are common amphetamine options, whereas Ritalin, Concerta, and Jornay, among others, are common methylphenidate options.

Nutraceuticals. Several nutraceutical products have been utilized to improve executive functioning, including bacopa, ginkgo biloba, lion’s mane, Rhodiola, SAMe, and L-theanine. An integrative psychiatry specialist can help you navigate through these nutraceutical options appropriately to determine what may be most appropriate based on your unique experience.

Bodily-Based Treatments. In the context of ADHD, a thorough investigation of the body should be conducted to reveal underlying causes and contributing factors. Addressing adrenal, hormonal, gut, detoxification, thyroid, immune, micronutrient, and epigenetic abnormalities is crucial in a holistic healing plan. Oftentimes, simple adjustments and support can make substantial differences.

Therapy. What follows are several options for therapy for those experiencing executive impairment or ADHD symptoms. Other psychotherapeutic techniques and modalities may be required for comorbidities. Psychotherapy for executive functioning, including those experiencing the symptoms of ADHD, is best guided by a tool exploring which executive functions could benefit from improvement.

Behavioral: Reward positive behaviors through positive reinforcement and intermittent scheduling. Periodically vary the rewards. Maintain consequences for negative behaviors. Clearly define acceptable and unacceptable behaviors. Clearly define rewards and consequences.

Problem-Solving Therapy: Guide the patient in exploring values, setting SMART goals related to those values, and breaking down action steps. Use successive approximation to achieve goals. Integrate organization and time-management principles. Implement self-reward systems for achieving steps on action plans.

Emotional: Teach emotion-regulation and mindfulness-oriented skills. Mindfulness actively builds on attention networks. Defuse from thoughts and emotions and practice acceptance.

Trauma-informed: A trauma-informed approach may help explore ADHD, which is causatively linked to childhood and developmental trauma. This is commonly overlooked in conventional practice.

Educational: The 504 plan can help with preferential seating, extra time on tests, and later for standardized testing (e.g., ACT or SAT). Consider an individualized education plan (IEP) for more support by spelling out everything teachers must do to help students succeed. Integrate a consultant for issues on the management of ADHD for teaching staff. Educate on health aspects of ADHD to schools and community.

Take Measures to Improve Your Executive Functioning Today.

-

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Asherson, P., Young, A. H., Eich-Höchli, D., Moran, P., Porsdal, V., & Deberdt, W. (2014). Differential diagnosis, comorbidity, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in relation to bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder in adults. Current Medical Research Opinion, 30(8), 1657-72. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2014.915800

Gaba, P. & Giordanengo, M. (2019). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: Screening and evaluation. American Family Physician, 99(11), 712.

Glind, G., Brink, W., Koeter, M. W. J., Carpentier, P., Ootmerssen, K. E., Kaye, S., … & Levin, F. R. (2013). Validity of the adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS) as a screener for adult ADHD in treatment seeking substance use disorder patients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 132(3), 587-596.

Kessler, R. C., Adler, L., Barkley, R., Biederman, J., Conners, C. K., Demler, O., … & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2006). The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States from the national comorbidity survey replication. American Journal of Psychiatry, 63(4), 415-424.

Michielsen, M., Semenij, E., Comijs, H. C., Ven, P., Beekman, A. T. F., Deeg, D. J. H., & Kooij, J. J. S. (2012). Prevalence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in older adults in the Netherlands. British Journal of Psychiatry, 2012(201), 298-305.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2018). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Diagnosis and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng87

Perugi, G. & Vannucchi, G. (2015). The use of stimulants and atomoxetine in adults with comorbid ADHD and bipolar disorder. Expert Opinion Pharmacotherapeutics, 16(14), 2193-204. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2015.1079620

Silk, T. J., Malpas, C. B., Beare, R., Efron, D., Anderson, V., Hazell, P., Jongeling, B., Nicholson, J. M., & Sciberras, E. (2019). A network analysis approach to ADHD symptoms: More than the sum of its parts. PloS one, 14(1), e0211053. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211053

Stahl, S. M. (2021). Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific basis and practical applications (5th Edition). Cambridge University Press.

Thapar, A., Cooper, M., Eyre, O., & Langley, K. (2013). What have we learnt about the causes of ADHD?. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 54(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02611.x

Ustun, B., Adler, L. A., Rudin, C., Faraone, S. V., Spencer, T. J., Berglund, P., Gruber, M. J., & Kessler, R. C. (2017). The World Health Organization Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Self-Report Screening Scale for DSM-5. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(5), 520–527. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0298

Viktorin, A., Rydén, E., Thase, M. E., Chang, Z., Lundholm, C., … & Landén, M. (2016). The Risk of Treatment-Emergent Mania With Methylphenidate in Bipolar Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(4), 341-348. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16040467